A Lonely Road

Building Community Amongst the Cars

By Amanda Gray

A couple of years ago, I volunteered with PVD Streets while they were implementing the Hope Street Temporary Trail.

You know it can be uncomfortable if you’ve ridden your bike or walked down Hope (Hope Street is among the top 10 corridors with the highest number of total bike crashes for 2009-21).. Even as a driver, pedestrian visibility is low due to parking on both sides of the street. The temporary urban trail aimed to make space for walkers, cyclists, wheelchairs, and anyone not driving a car by moving designated parking to only one side of the street.

While spray painting mini bicycles and little figures on roller blades for sharrows in the freshly minted-bike-walk-roll-lane, a large SUV came flying past, the driver screaming, “You should be ashamed of yourselves!”

For the more seasoned transportation activists, the aggression was expected. They shrugged it off. But that moment lived in my head for a while. Ashamed of what I wondered?

Design with (only) cars in mind

While opinion in the United States has shifted in recent years, marked by a growing demand for public transport, it’s commonplace, even expected, for criticism of car culture to be met with pushback and even antagonism. The enduring narrative that cars are essential to social and physical upward mobility has been hard to shake.

For Peter Norton, a historian in the engineering department at the University of Virginia and the author of Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City, the resistance toward more pedestrian-friendly cities is understandable, even if it’s not in our best interests. “It’s very common for people to tell you, ‘Well, the status quo that we have today was because of consumer choice or democratic processes.’ but I don’t think that’s accurate at all,” he says.

Norton, who drives a vehicle in addition to biking and walking whenever possible, also cites the struggle during the post-war economic boom against rapid suburbanization and the subsequent decimation of a robust public transit system as being largely forgotten. “Nobody actually voted for car dependency,” concludes Norton.

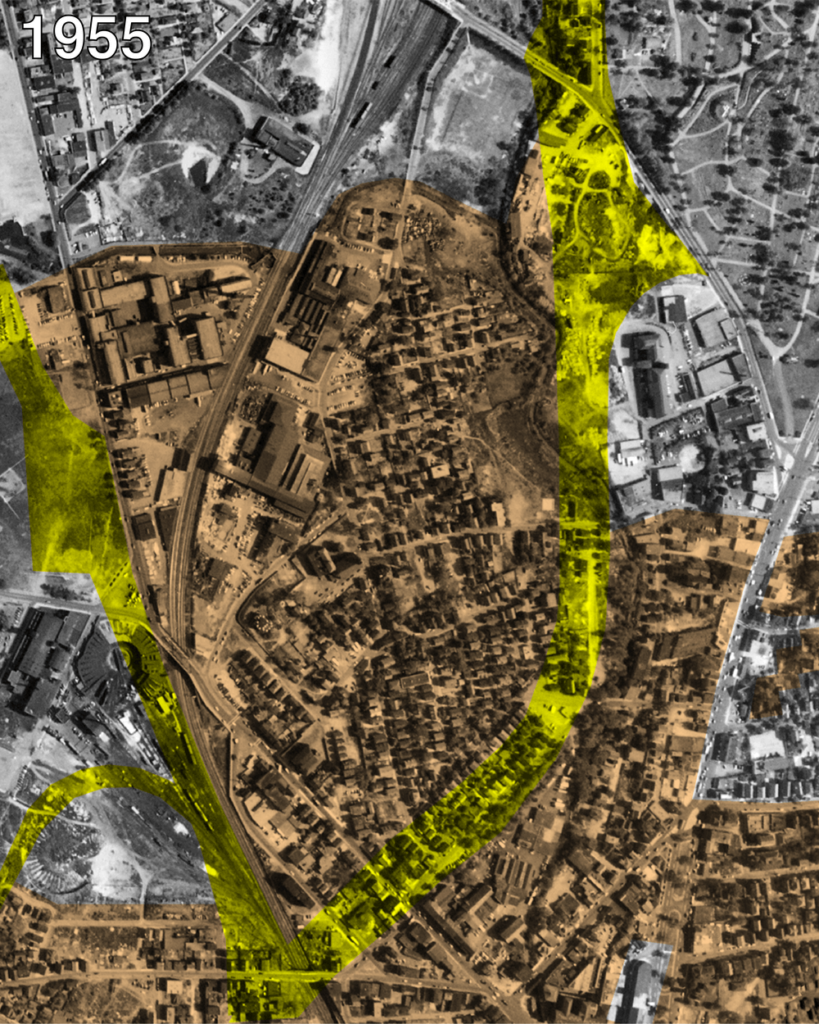

The Highway Revolts in the 1960s and ’70s stopped some major projects (like a freeway severing San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park and the Inner Belt project in Boston). However, auto manufacturers and highway lobbyists still managed to inflict serious damage. “Looking back, we can see what amazing public transport systems and walkable communities we had, which we not only lost but actively destroyed,” says Norton.

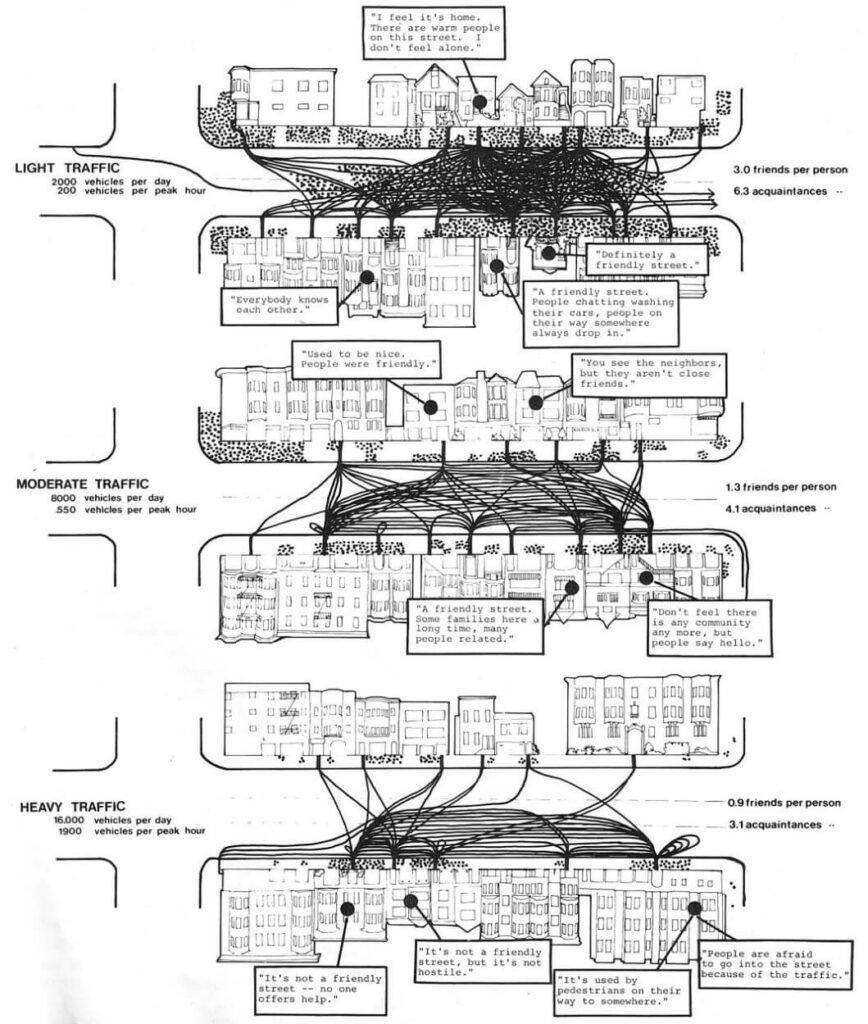

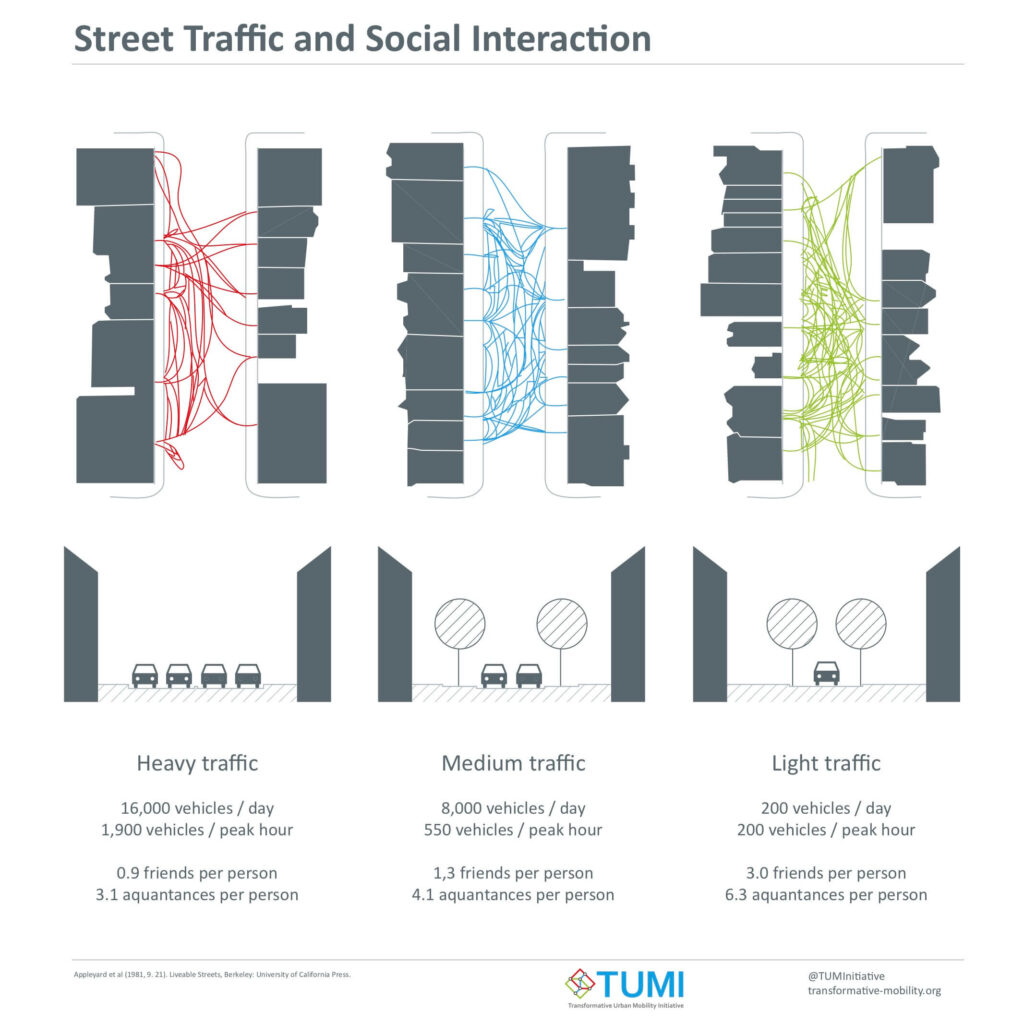

This destruction and subsequent outcomes came to light in the groundbreaking 1981 Publication Livable Streets. An urban planner and activist whose work took a humanistic approach, Donald Appleyard pioneered community-based planning, demonstrating the harmful effects of car-dominated communities, from carbon emissions and noise pollution to reinforced segregation, socioeconomic inequality, and social isolation. Appleyard’s work came to a halt when he was killed by a drunk driver in Athens, Greece. His legacy, though, has been carried on by his son, Bruce Appleyard, who has followed up with Livable Streets 2.0.

Most car-free (or car-lite) living advocates understand eliminating cars isn’t a straightforward (or even desirable) solution to the declining quality of life in the United States. But, to understand how we got where we are today, it’s important to comprehend the myriad adverse effects on our physical and social well-being due to car dependency. “There’s no question that we have a self-imposed epidemic of social isolation,” says Norton. “I say “self-imposed” as the so-called experts and the authorities decided many decades ago that we should have everyday destinations far from where people live.”

Car dependency leaves many behind

Even though Americans are driving less, a stigma is still attached to those who don’t. For a country all about freedom of choice, we certainly don’t like it when someone makes the perceived wrong one. Not having a driver’s license is often seen as a character flaw, a sign of laziness and helplessness, something reserved for those living in poverty.

A Gallup Poll in 2018 found that 6% of Americans don’t drive. Based on the population at the time, around 2 million people were without a driver’s license. That same study found that the typical driver was a male college graduate between 39 and 50 years old, living in the suburbs and making approximately $90,000 a year. Social stigma, plus inadequate representation of the various groups of people who don’t (or can’t) drive, leaves many older adults, people with disabilities, and children at risk of being left behind.

“It’s like we build these ultimate challenge courses,” says Dan Burden, who served as the first state bicycle and pedestrian coordinator for the Florida DOT, co-founded Walkable Communities, and is currently the director of innovation and inspiration at Blue Zones. Drawing on his professional and personal experience, Burden points out that many older people struggle with their physical balance, which can prove dangerous when walking on cracked and raised sidewalks. Sidewalks in American cities have fallen into disrepair. Many developers aren’t required to build them in residential areas, making it near impossible for someone to use a wheelchair, walker, or anything but their own two feet. Simply going for a walk can be a challenge, resulting in less social interaction daily.

Holly Snyder, an AARP Rhode Island Advocacy volunteer and dedicated public transit user, regularly took the bus to work during her 18 years at Brown University. Due to the lack of parking space, Brown offered staff RIPTA passes to encourage workers to drive less. Snyder, who has a driver’s license, opted for walking or taking the bus, which she credits to keeping her connected. “Riding the bus gives you a sense of who lives in Rhode Island and gives you a sense of your neighborhood, says Snyder. “It’s a way of being part of your community that’s impossible if you’re in a car.”

For Snyder, now retired, daily social interaction is fundamental to well-being. “It’s understood that some of our most important social interactions aren’t necessarily with good friends or intimate partners but with the cashier at the store. Causal conversations where you connect with another person don’t have to be deeply meaningful, but a way to maintain a sense of connection with your neighbors and build community.”

A study published in the Journal of Aging and Health showed that older adults had a two-fold increase in experiencing social isolation following a period of driving cessation, which isn’t just lonely but a health hazard. “If you have a routine eye exam or any kind of surgery where they give you a sedative, they don’t want you in a car,” says Snyder. With more than a quarter of households having just one person, Snyder points out that medical transit is a huge issue “nobody’s addressing, and it’s only going to get worse with more people living alone.”

And it’s not just older adults; car-centric communities negatively affect children, who are eight times more likely to be killed by commonplace vehicles like SUVs than passenger cars. Dangerous roadways and a lack of green space result in adults driving kids to safe places to play, like a park or boulevard. For Burden, creating neighborhood meeting places can help reestablish a community. “In Victoria, Australia, they ensure that there is a park within an ⅛ mile of every home, says Burden. “They don’t have to be big, he continues. “They just need nature, fun things to do, and serve as a place for people to meet.”

No life in the fast lane

In the last twelve months, three pedestrians were killed on North Main Street, one of Providence’s central arterial roads, paralleling I-95. The speed limit is 25 mph, but with wide lanes and long straightaways, most drivers are going well over. These incidents have been treated as tragic one-offs rather than systemic issues. In 2022, an estimated 7,508 pedestrians were killed by motor vehicles in the United States, a number not seen since 1981.

“We’ve created the conditions where fewer people are outside and are now in a dynamic totally against human needs,” says Burden when discussing speed as a critical pain point in the current design of cities and towns. Arterial thoroughfares like North Main, sometimes called “Stroads” by urbanists, are undeniably unsafe, resulting in decreased social cohesion. Home to the densely populated Summit neighborhood and amenities like restaurants and supermarkets, residents living near North Main should be able to walk to pick up groceries or meet a friend for coffee. Yet, poor design has resulted in dangerous conditions that make walking in the area a nightmare.

A study by Ian Walker, a professor of environmental psychology at Swansea University in Wales, found that people tend to normalize antisocial behavior associated with driving. Walker and his team call this phenomenon “motonormativity,” colloquially known as “car brain.” The study asked participants to answer questions that compared driving to other daily activities. The study showed an inherent double standard applied to driving. For example, only 21% of participants agreed that risk was a natural part of working, while 61% decided that risk was an inherent “part of driving.”

Burden believes traffic calming is the “magic sauce” for generating lively, healthy communities. Beyond building speed bumps, which can be hard on cars, wider sidewalks, raised intersections, and tree-lined streets make streets pleasant for walking, open-air dining, and accessible to people with disabilities.

Small steps, significant changes

Organizations like Strong Towns, which address “the failures of the post-war North American development pattern,” encourage people to get together to take the power back. Strong Town’s Community Action Lab and The Crash Anlysis Studio encourage experts and residents to work together to create more socially cohesive, livable communities. These changes, according to Erfurt, Director of Community Action at Strong Towns, “don’t have to be cost-prohibitive or rely on outside funding,” says Erfurt.

Tactical urbanism employs reversible pop-up projects, like parklets or outdoor dining, which helps address reluctance to creating pedestrian-friendly spaces by allowing people to experience the benefits of car-free spaces rather than making a judgment based on unknowns. In the case of the Crash Course Analysis tool, community input changes the narrative of why car crashes occur and goes “beyond the myth of “driver error,” providing a life-saving new framework preventing deadly crashes.

One of the famous examples of strategic change in urban space was the former commissioner of the New York City DOT, Jeanette Sadik-Khan, who decided to place 376 beach chairs in NYC’s Times Square. The experiment freed up space for pedestrians to sit and relax in a typically congested, loud, and dangerous area. Eventually, 100,000 square feet in Times Square became pedestrian-exclusive. Since then, pedestrian injuries have dropped by 40%, in addition to auto accidents and crime, while pollution rates have fallen as much as 60%.

Erfurt believes people genuinely want fewer cars and more walkable communities. However, he stresses the importance of starting small. “People are afraid of change,” says Erfurt, without judgment. “Consistent, incremental changes are effective when addressing big problems.” Erfurt referred to recent examples of community engagement, like one in Chisholm, Minnesota, where residents transform a public space with a salon chair and materials to support a community member looking to open their own business.

Finding Hope on Hope Street

While the Hope Street Temporary Trail was not permanently implemented, 53% favored the trail as a permanent fixture, noting in surveys taken throughout the week that equity and accessibility were top concerns.

For one week in October, children would begin their day safely biking to school, and those getting some early exercise could enjoy a walk or run without rubbing shoulders with speeding cars. In addition to a week of stress-free riding, skating, and a general uptick in pedestrian traffic, the temporary ramps made it easier for pedestrians and wheelchair users to get on and off the bus. Despite the occasional rain shower, and some resistance from businesses and residents, the trail successfully sparked conversations, expanded mobility, and fostered community engagement.

Definitely nothing to be ashamed of.

Amanda Gray is a multidisciplinary writer and artist based in Providence. https://www.clippings.me/amandasgray